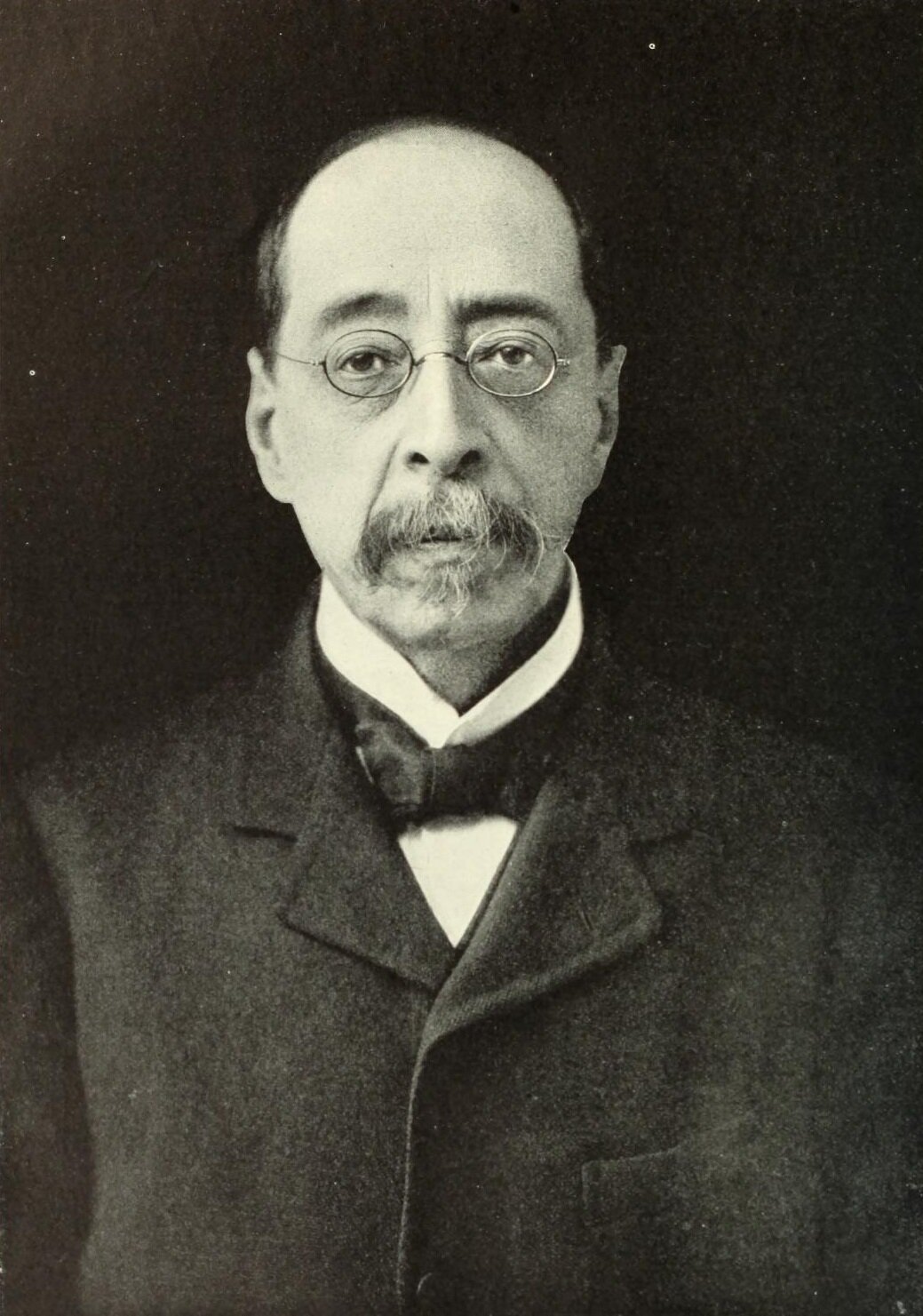

John La Farge

Tonalism owes much of its earliest principles to an underrated (because hard to classify) nineteenth-century American artist, John La Farge.

By Chistopher Volpe

John La Farge

A student of William Morris Hunt, La Farge succeeded as a painter (oil, watercolor, encaustic), muralist, lecturer, stained glass window maker, decorator, and writer. He invented techniques in stained glass that opened new directions in the art while rivalling the richest craftsmanship of the ages. (La Farge devised a method of illuminating opalescent glass, which had never before been created in sheets, and taught the technique to Louis Comfort Tiffany, with whom he then spent the next decade in a patent dispute over the process).

As a painter, La Farge ranged among still life, landscape, portrait, and works in the Symbolist style, always driven by an original, innovator’s spirit. He was among the first American painters to incorporate the seminal lessons of Japanese printmaking into painting (he published the first book on Hokusai in America). From Hunt he learned the innovations of mid-century French Barbizon painting, which he distilled and synthesized for a new kind of American painting that would be called Tonalism.

Moving his family to a little town called Paradise, near Newport, Rhode Island, La Farge studied at an art school Hunt had established. Decades before it became a fashionable zip-code, Newport was a landscape of misty, rather desolate seaside hills, with “a narrow a range of color and form,” as Henry James (also drawn there) wrote, and “a combined loveliness of tone, as painters call it.” This Brittany-like outpost of refined light and color encouraged the American artists to minimize the Grand Vista in favor of, as La Farge later said, “the rendering of the gradations of light and air through which we see form.” Within months, La Farge had absorbed Hunt’s knowledge of the Barbizon approach and begun experimenting and extending it in ways that Hunt himself never would.

Two years in the making, La Farge’s 1866-68 Paradise Valley was boldly modern. When it was finally exhibited in 1876, critics alternately balked at and extolled its elevated horizon line, willfully rough brushwork, and the “enormous tour-de-force” needed to turn such a relatively bald, featureless landscape into a “study of nature,” as La Farge insisted it was. It was utterly unlike anything being painted by the dominant Hudson River School.

“No American master, ever laid paint on so, or made it express this faint haze and respirable warmth” said The Nation, “from Cole and Doughty to Cropsey, Kensett, and Church—.” (“Fine Arts. The National Academy Exhibition II,” The Nation22 (April 20, 1876): 268, cited by the Terra Foundation for American Art,

Paradise_Valley, John La Farge 1866_1868, Museum of Fine Arts - Boston

Seldom if ever had such a large picture of such an ostensibly empty stretch of scenery had within it so little – and so much – going on at once. Painting such a large canvas (32 5/8 x 42 in) in nature, directly from observation, was in itself unusual. The Barbizon painters generally worked small; they were painting against the clock in the changing light of nature. La Farge painted Paradise Valley on location as well, but he rejected picturesque scenery to foreground nuances of color, atmosphere, and effect – subtle and haunting variations of tone.

Most of the canvas is taken up by vast amounts of pasture composed of meticulously observed and expertly modulated variations of green and ocher. La Farge was implicitly making a statement, a new note in American painting – that “copying nature,” as he called it, and transforming the ordinary through the lens of personal vision (soul, spirit, poetry) he might have added, could produce beautiful paintings worthy of the most serious consideration. The groundwork for Tonalism had been laid, and artists like his later studio mate homer Dodge Martin, Alexander Wyant and George Inness, surely took note of his subtle harmonies of tone and vibration and his evocation of the spiritual within the everyday. Later critics and artists emphatically celebrated the painting for the revolutionary pre-Impressionist masterpiece it was.

La Forge’s paint handling surely looked unfinished at the time, but La Farge has advice for painters that rings true today more than ever: The end of painting, he wrote, is “to express what you care for most by the simplest means that will avail you - your personality, your knowledge, your experience; whether you do it in work that takes years, or whether you do it, like Caran d’Ache, in the line of a few seconds.” - John La Farge (Considerations on Painting, New York, 1893).

Snow Field John a Farge, 1864,, The Art Institute of Chicago